What are a director’s duties?

The Companies Act 2006 sets out seven core duties (ie directors’ duties) that apply to every statutory director. Most of these obligations are fiduciary duties, which arise from the relationship of trust and confidence directors have with the company. This relationship places a core duty on directors to act in the best interests of the company, with good faith and honesty. You must always put the company’s interests ahead of your own personal interests.

The seven statutory duties are:

Duty to act within powers

You must act according to the company's articles of association and only use your powers for the reasons they were given. For instance, if the articles state that shareholders must approve a major loan, you can't approve it yourself without them.

Duty to promote the success of the company

This is often called the enlightened shareholder value (ESV) duty. You must act in a way you believe, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the company's success for the benefit of all its shareholders. When making decisions, you mustn't forget to consider a number of factors, including:

-

the likely consequences of the decision in the long term

-

the interests of the company’s employees

-

the need to foster business relationships with suppliers, customers, and others

-

the impact of the company’s operations on the community and the environment

-

the desirability of the company maintaining a reputation for high standards of business conduct

-

the need to act fairly between the company's members

Duty to exercise independent judgement

You must make your own decisions. You shouldn't blindly follow the instructions of others, such as a major shareholder or even another director. However, this duty doesn't stop you from acting in line with a formal agreement the company has already entered into, or when taking professional advice. You just have to use your own informed judgement when deciding whether to follow that advice.

Duty to exercise reasonable care, skill, and diligence

This is the duty of care and skill. It requires you to act with a certain level of competence while fulfilling your role. Specifically, you must exercise the care, skill, and diligence that would be exercised by a reasonably diligent person, taking into account two standards:

-

the minimum standard - the general knowledge, skill, and experience that may reasonably be expected of a person carrying out the functions of the director in relation to the company (ie the minimum level expected of any director)

-

the subjective standard - the general knowledge, skill, and experience that you actually possess (ie if you have specialist knowledge, such as legal or accounting expertise, you’re expected to use it)

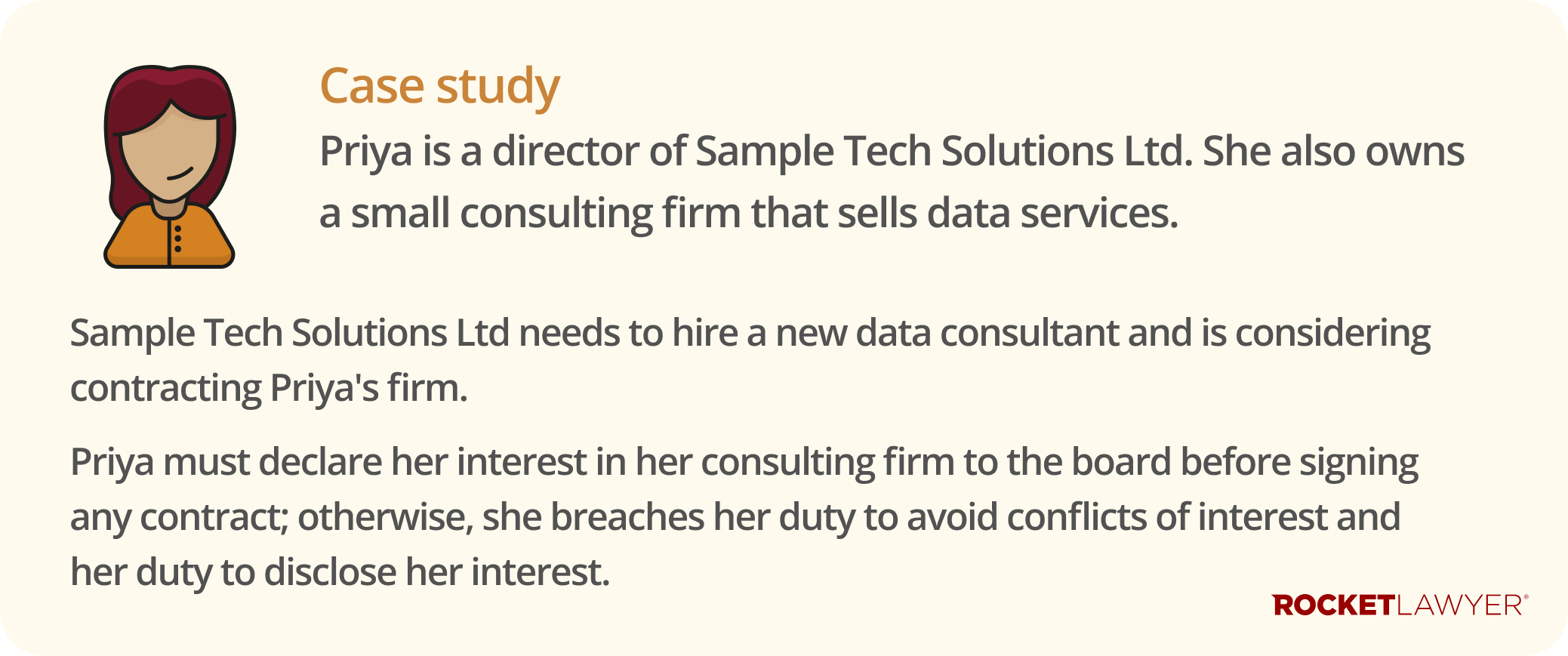

Duty to avoid conflicts of interest

You must avoid any situation where your personal interests clash, or may possibly clash, with the company’s interests. This includes exploiting any property, information, or opportunity belonging to the company. If a conflict arises, you usually need the authorisation of the board or the shareholders to proceed.

Duty not to accept benefits from third parties

You can't accept gifts, inducements, or other benefits from a third party because you are a director, or for doing (or not doing) anything in that role. This rule is designed to ensure your independence isn't compromised by outside influence.

Duty to declare interest in proposed transactions

If you’re directly or indirectly interested in a proposed transaction or arrangement with the company (eg if the company plans to buy a piece of equipment from a company you control), you must declare the nature and extent of that interest to the other directors before the company enters into the transaction.

Who do directors owe the duties to?

You owe all directors’ duties to the company itself. This is a fundamental principle of company law: you are the agent of the company, which is a separate legal entity from its owners, the shareholders. Therefore, you don't owe these duties directly to shareholders, employees, or any other third party.

However, this rule changes if the company is facing financial difficulty or is insolvent. In that situation, your duty to promote the company's success shifts, and you must primarily consider the interests of the company’s creditors to avoid causing them further loss. These interests will need to be balanced with those of the company, especially in the early stages when insolvency is not yet inevitable.

How long do directors owe the duties for?

A director owes the general statutory duties to the company from the moment of their appointment. For most duties, the obligation ends when the director formally resigns or is removed as company director.

However, the law imposes two key duties on ex-directors to prevent them from immediately exploiting company knowledge or opportunities they gained while in office. Specifically, the duty to avoid conflicts of interest and the duty not to accept benefits from third parties continue to apply after a director resigns, but only in respect of opportunities, acts, or omissions that occurred while they were a director.

Who can bring a claim for breach of the duties?

Since the duties are owed to the company, it’s the company that generally has the right to bring a claim against you for a breach. The board of directors is typically responsible for making this decision, or, in the event of insolvency, the liquidator.

However, if the board won't act, a shareholder can sometimes take legal action on the company’s behalf through what’s called a derivative claim. This is a court application that allows a shareholder to sue a director for a breach of duty or negligence. The court must grant permission for a derivative claim to proceed, and it will check that the shareholder is acting in good faith to benefit the company. Ask a lawyer for more information.

What happens if a director breaches their duties?

The consequences of breaching your director’s duties can be severe and may result in immediate dismissal from your role.

If the breach involves serious misconduct, such as bribery or fraudulent trading, you can be held personally or criminally liable. The court can order various civil remedies against you personally, depending on the severity and nature of the breach.

If you’re found to be in breach, you might have to:

-

pay compensation (ie damages) to the company for any loss it suffered because of your actions

-

return any personal profit you made as a result of the breach (eg profits from an undisclosed conflict of interest)

-

reverse a transaction, such as having a contract set aside

A major consequence of breaching your duties is the risk of personal liability, especially if the company becomes insolvent. If you continue to trade when you knew, or ought to have known, there was no reasonable prospect of avoiding insolvent liquidation, you could be liable for wrongful trading. You could also face disqualification from acting as a company director. For more information, read Disqualification of company directors.

How can directors be protected?

The Companies Act 2006 prohibits directors from being exempt or indemnified against liabilities in connection with any negligence, default, breach of duty, or breach of trust. However, in the event of a breach of the directors’ duties, directors can be protected by:

-

obtaining insurance (eg directors and officers insurance) to cover legal costs, defence costs, and potential compensation payments arising from claims made against you personally

-

ensuring the company provides an indemnity against certain liabilities incurred to third parties (though it can't cover things like criminal fines)

-

seeking shareholder ratification (ie shareholders vote to approve your action after the fact) for negligent actions or breaches of duty (this releases you from liability to the company, but not to third parties, and doesn't apply to illegal acts)

-

applying to the court for relief if you've acted honestly and reasonably and ought fairly to be excused, considering all the circumstances (however, this is viewed as a last resort, as courts are generally reluctant to grant it)

What steps should directors take to demonstrate compliance?

To demonstrate that you’ve complied with your duties, especially the duty to promote success and the duty of care and skill, you should ensure that you:

-

keep up-to-date accounting records and reports

-

prepare a director's report providing information on the affairs of the company

-

keep Minutes of board meetings to record decision-making (this documentation helps ensure you consciously think about your duties when making decisions on behalf of the company)

-

follow the proper procedure for all major company actions

For more information on the expected conduct and responsibilities of your role, read The role of a company director and Misfeasance and insolvency.

If you’re unsure whether a transaction, decision, or personal interest might compromise your duties, the safest course of action is always to disclose it fully to the board. Do not hesitate to Ask a lawyer if you have any questions or concerns about directors’ duties.