What is mental capacity?

Mental capacity is the ability to make specific decisions when necessary. Someone will be considered to have mental capacity if they understand a decision they need to make, why they need to make it and the likely outcome of the decision.

Under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA), people are presumed to have capacity unless proven otherwise. The MCA sets out a 2-stage test to establish whether someone lacks mental capacity:

-

does the person have an impairment of their mind or brain ( as a result of an illness, like dementia, or external factors, like alcohol, drugs or trauma)? Such impairments may be temporary

-

Does this impairment mean the person is unable to make the specific decision that needs to be made when they need to?

For more information on mental capacity, see the NHS guidance on the MCA.

When will I not have mental capacity?

It’s important to note that people can lack capacity to make some decisions but have capacity to make others. Further, someone’s mental capacity can fluctuate and change with time, and people may lack capacity at one point before being able to make the same decision later.

Generally speaking, someone will lack mental capacity and be unable to decide for themselves if they cannot:

-

understand information relevant to the decision

-

retain and remember the information

-

use (eg evaluate) the information as part of the decision-making process

A lack of mental capacity may be:

-

permanent - this is where your ability to make decisions is permanently affected (eg because you have dementia or a brain injury)

-

short-term - this is where your ability to make decisions changes from day to day (eg because you’re unconscious or are experiencing confusion as a side-effect of any medication you’re taking or if you have dementia that presents differently at different times)

For more information on mental capacity, see the NHS guidance on the MCA.

Note that if you’re able to make a decision but unable to communicate it, you may also be deemed not to have mental capacity to make that decision.

How does mental capacity relate to making legal documents?

There is a presumption that everyone has the capacity to enter into a contract. However, this presumption can be rebutted in certain circumstances and, when this occurs, the contract will not be enforceable. Someone will not be considered to have the capacity to enter into a contract if they are a minor, don’t have the necessary mental capacity or are drunk to the point where they are incapable of understanding what they are doing. If you entered into a contract but lacked the capacity to do so, it will generally be up to you to decide whether or not to invalidate the contract. For more information, read How to form a valid contract.

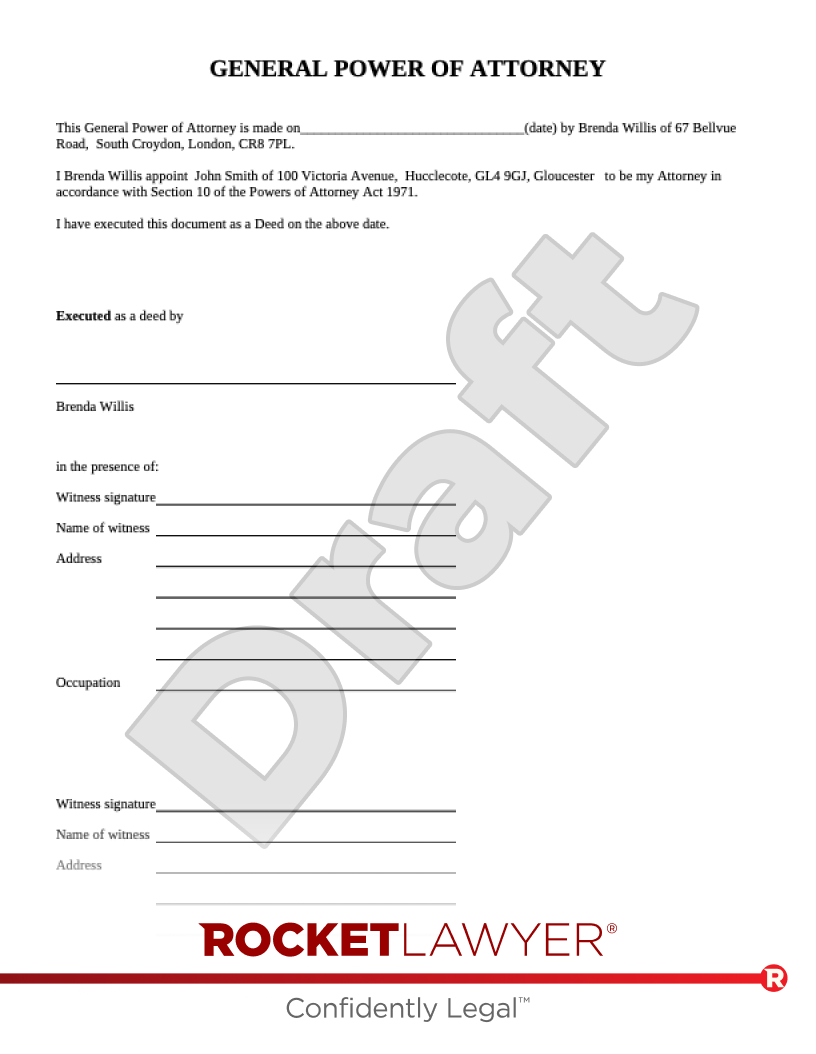

It’s also important to note that certain legal documents are designed to help you make advanced decisions in case you lose mental capacity. These documents, provided they are made when you are of sound mind, provide a clear record of your wishes and should be followed. These types of documents include:

-

Last wills and testaments - which set out someone’s wishes for how their estate (ie their property and belongings) should be distributed after their death. For more information, read Reasons to make a will

-

Codicils - which can be used to make minor changes to existing wills. For more information, read Codicils

-

Lasting powers of attorney (LPAs) - which allow someone to appoint an ‘attorney’ to deal with their property and financial affairs and/or make health and welfare decisions on their behalf. For more information, read Lasting powers of attorney

-

Living wills - which state someone’s wishes about how they wish to be looked after if they lose their mental capacity, especially if they do not want to receive life-sustaining treatment. For more information, read Different types of will documents

What is medical consent?

Medical consent is a fundamental part of medical ethics and international human rights law. It refers to a person’s agreement to receive any type of medical procedure, treatment, intervention or examination. A patient’s consent is generally always needed regardless of the procedure in question - it’s needed for things as simple as touching someone’s skin to judge their temperature.

When is medical consent valid?

Medical consent will be valid if:

-

it was given voluntarily (ie the decision to provide it was made by the person without any undue influence or pressure from anyone else, including family, friends and medical staff)

-

consent was informed (ie the person had all necessary information about the procedure/treatment, including risks and benefits, any alternative procedures/treatments and the consequences of not having the procedure/treatment), and

-

the person giving their consent had mental capacity

If an adult (ie someone over the age of 18) has the mental capacity to make a voluntary and informed decision, this decision must be respected. This includes situations where they refuse treatment and applies to situations where their refusal may result in their death or the death of their unborn child.

If someone lacks mental capacity but has an LPA in place, their attorney can make medical decisions on their behalf. If someone lacks mental capacity but has a living will in place, the wishes set out in their living will should be respected. If someone does not have a living will in place and is placed on life support, decisions about continuing or stopping treatment is generally a decision for the person’s family (and potentially friends) to make after consulting with medical staff.

For more information, read the NHS guidance on consent to treatment.

How is medical consent given?

Medical consent can be given verbally (eg by telling a medical professional that you are happy to receive an X-ray) or in writing (eg by signing a surgery consent form). This may also be referred to as ‘explicit consent’.

In some situations, consent may also be given non-verbally (eg by nodding, opening your mouth for a dental exam or sticking out your arm for a blood test), provided the person providing their consent understands the procedure/treatment in question. Non-verbal consent may also be referred to as ‘implied consent’ or ‘implicit consent’.

Medical consent should be given to the medical professional who is responsible for your medical treatment. For example, your GP (if they’re prescribing medicine), a surgeon (if they’ll be operating on you) or a nurse (if they’re arranging a blood test or examination).

For major procedures (eg surgeries), medical consent should be secured in advance. This ensures that the person receiving the procedures fully understands the procedure in question and has plenty of time to ask any questions they may have.

Consent can be withdrawn at any time.

For more information, read the NHS guidance on consent to treatment.

When is medical consent not needed?

There are certain situations where medical consent does not need to be obtained. This includes situations where the person is able to give consent but may lack capacity. Examples of situations where healthcare professionals may not need to get consent from someone before treating them include when they:

-

need emergency, life-saving treatment but are incapacitated (eg unconscious)

-

immediately need another emergency procedure during surgery and it would be unsafe to wait for their consent

-

have a severe mental health condition (eg schizophrenia) and lack mental capacity to consent to treatment for their mental health

-

are severely ill and living in unhygienic conditions (under the National Assistance Act 1948)

For more information, read the NHS guidance on consent to treatment.

What about medical consent for children?

Children between the age of 16 and 18 can provide medical consent for themselves. This is because they are presumed to have the capacity to decide on their own medical treatments.

Children under the age of 16 can provide medical consent for themselves if they have ‘Gillick competence’. The Gillick competence test assesses an under-16’s capacity to understand the nature, purpose and potential consequences of a proposed treatment, as well as the risks and benefits involved. If they demonstrate sufficient understanding and competence, they may be considered legally competent to provide (or withhold) medical consent independently. For more information, read the NSPCC guidance on Gillick competency.

Medical consent can be provided on behalf of a minor who does not have Gillick competence by someone with parental responsibility (eg a parent) for them. This person with parental responsibility must have mental capacity.

The Court of Protection can overrule a refusal for treatment of a minor if it is in the minor’s best interests. This includes situations where someone with parental responsibility refuses treatment, where a minor between 16 and 18 refuses treatment or where a Gillick-competent minor refuses treatment.

For more information, read the NHS guidance on consent to treatment for children and young people.